The Pacific Northwest Magazine, The Seattle Times, February 15, 2004

WORK & PLAY

For a passionate piano man, there's room to have it all

Written by Lawrence Kreisman, program director for Historic Seattle and author of "Made to Last: Historic Preservation in Seattle and King County." Photographed by Barry Wong a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer

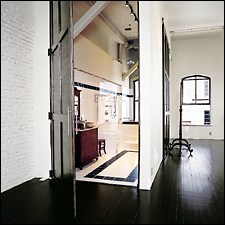

Arched windows in the living area open to city and waterfront views. Acquired and inherited pieces include the daybed and artwork.

Pianos and piano parts are everywhere. Biedermeier, Empire, Renaissance Revival, Neo-Classical. In ebony and rosewood, from simple to ornate. Standing on their own three feet and stacked on their sides, turned and upside down suspended from the ceiling. Three floors of pianos in various states of repair. Is it a warehouse? A workshop? A concert hall or a home? For Obi Manteufel, it is all four.

Pianos have been a large part of this pianist's life for as long as he can remember. But playing led to collecting, and it's hard to imagine anyone in the Northwest with a larger collection.

Manteufel moved to Tacoma from Bainbridge Island where, in 2,000 square feet of living space on two levels, he managed to house a workshop and half a dozen pianos; others were stashed in a building on Stone Way in Seattle. He owns acreage on Hood Canal but has yet to plan a house there. Instead, he decided to move to Tacoma.

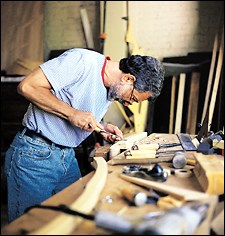

Obi Manteufel enjoys the light-filled workshop on the Broadway side of the second floor.

The brick building he bought four years ago is just down the street from the restored Rialto and Pantages theaters. Built in 1889 on a sloping site, it has ground- and first-floor entries on two streets. Researching the building, he discovered that it served as city court offices for two years before it became home to the Tacoma Cracker Co. Manteufel displays a collection of old photographs of the building and neighborhood in the early years, showing streets with wood-plank sidewalks connected by bridges. There was a side yard next to his building where the Kress store eventually was built. A sky-lit side-entrance stair — long gone — led to the yard.

By the time Manteufel saw it, the building had been vacant for some years. Badly damaged lath and plaster covered its brick walls. One stack of windows facing the alley at the back was obscured by an old dumbwaiter. But the structural integrity impressed him. Manteufel shows off 2-inch-thick rough-sawn fir beams bolted with steel straps and set back into the brick. Though it was clear the building had been through lots of earthquakes, the city required a substantial seismic retrofit, which accounts for new steel beams and posts that frame the rooms.

A London-made Erard grand is the piano of choice for Manteufel's living space. The kitchen has stock cabinetry.

In order to adapt the space for his use, Manteufel relocated stairways, insulated the end walls for comfort, stripped ancient linoleum flooring and restored all the original windows. The size of windows on the second floor made it the best place for a workshop. The center of the ground floor — Manteufel calls it "the sweet spot of the building" — has become a performance area for impromptu concerts. The back of this floor has no windows — it sits under the sidewalk to the alley — making it just right for a large bathroom.

With 3,500 square feet on each floor, Manteufel has an extraordinary amount of living and working space. The top is informally divided by its furniture into entertaining, dining, kitchen, study, workspace, bathroom and bedroom. The ceiling heights rise from 18 to 21 feet because of the roof slope. The bathroom — at the tallest end — sports an oversized 13-foot-tall door as well as a set of doors that open one wall to let in light from other windows.

Rows of piano legs suspended along the upper wall represent several centuries and many design styles.

Manteufel was purposeful in doing improvements that would be effective without being costly because he didn't know how long he'd be here and assumed that new tenants would probably tear out his improvements to make their own. For instance, he purchased ready-made maple cabinets from Ikea for his kitchen rather than look into custom work. He has furnished the space with heirlooms he inherited or collected for years. Pointing to several Renaissance Revival sideboards that belonged to a dear relative, he says, "They represent nostalgia rather than reflecting my own personal taste. This is the first time they have been out of storage — they were too big and bulky for the Bainbridge Island house."

Partly opened, a 13-foot-high door reveals the tiled bathroom and hot tub beyond.

There is only one piano on this floor, an 1859 Blüthner made in Leipzig. The rest — 38 of them — occupy the ground and second floors. "I bought a great many of them in the late 1970s. I had relatives in the import-auction business, so I was able to afford them for next to nothing. The earliest was made in 1793. I have concert grands, early London Erards, two Vienna Bösendorfers from the first years of their production — the kind that Lizst performed on, early London Broadwoods, and an early straight-strung Steinway."

The restoration, repair and rebuilding of these instruments seem to him a natural outgrowth of his playing. "Pianos are wood and felt and leather and watchmaker tolerances." They constantly need attention, he continues. "You learn to file and hand-shape hammers — they get deeply cut by the strings. And of course it's just the next step to gluing up your own hammers. When I was in Europe studying and traveling, I went to factories and talked to the oldest employees there to learn their methods."

Manteufel is clearly pleased with his "interim" location. "I like being above the shop. I don't have to go anywhere," he says. Looking out his second-floor workshop windows, he points to his view of the city, to the park across the street where he walks his dog, and the waterworks that define that park. "With the windows open at night, the water sounds like it does on the beach at Bainbridge."

Lawrence Kreisman is program director for Historic Seattle and is author of "Made to Last: Historic Preservation in Seattle and King County." Barry Wong is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer.